This is a topic that comes up quite infrequently for many people and for most, never. It’s also one of the topics that is significantly more complex than it should be and one that is fairly poorly documented online about how to do this properly. Fundamentally this is a basic Copy & Paste exercise at best, but it’s made ridiculously complex by the underlying technical gubbins. So hopefully this blog post can clear up the steps involved and some of the considerations you need to make.

Old and New Disks

Disks come in many different shapes and sizes both conceptually and physically, with varying connectors and different underlying technologies. The nuances of these are beyond the scope of this blog post, but to put a few basics down to help conversation let’s look at a few of these at a high level.

We’ve previously covered off topics on the Performance of SSDs VS HDDs so take a look at that for some handy background info.

Summary being that you essentially have two types of hard drives;

- Mechanical Hard Disk Drive (HDD) – Has moving parts

- Solid State Drives (SSD) – Has no moving parts

See the above blog post for further insights into the differences.

Anyhow, the important point being for the purpose of cloning a hard disk is that you need to know the details of what you are going from and what you are moving to. Get this wrong and you can seriously mess things up in a completely un-recoverable way, so please be careful and if you aren’t sure what you are doing, don’t proceed and instead pass this onto a professional to do this for you.

Disk Connectors – IDE VS SATA

For the sake of simplicity, the two core connectors for disk drives fundamentally fall into either IDE (old) and SATA (new). Yes, the teckies who are reading this will say that this is garbage, and it is. But, in reality, for those reading this blog post, this is likely going to cover 99% of the use case.

In reality there are many types of disk connectors from PATA, SATA, SCSI, SSD, HDD, IDE, M.2 NVMe. M.2 SATA, mSATA, RAID, Host Bus Adapters (HBA) and more (and yes, not all of these are technically connectors… but for the sake of simplicity, we don’t care for this blog post). At the time of writing, the majority of people using the many other various types of disk connectors outside of the basics are generally going to be working within corporate enterprises which tend to operate on a bin and replace mentality from a hardware perspective for basic user computers and for data centres and server racks have setup with cloud native data storage with high availability and lots of redundancy. For many smaller organisations and/or personal use case, this is a goal to work towards.

Which is why we are covering this topic for the average user to help to understand the basics for how to clone a hard disk either if you are upgrading and/or are trying to recover data from a failing disk.

Adapters

Ok, so we’ve covered off the different types of hard disks, it’s time to look at how we connect them to a computer to perform the data migration. Here is where we need the correct connectors to do the job, and this isn’t straight forward.

For simplicity and ease, USB is likely to be the easiest solution for the majority of use cases. Note there is a significant difference in USB 1.0 VS USB 2.0 VS USB 3.0 when it comes to performance and to add to the complexity, there are also different USB Form Factors (aka. different shapes of the connector, but fundamentally doing the same thing) which adds to the confusion.

I work in this field, and I am continually surprised (aka. annoyed…) by the manufacturers who continually make this 1000x more complex than it needs to be. I for one am extremely happy that the European Union (EU) has decided to take a first stance on this topic to help to simplify the needless complexity by standardising on a single port type for charging devices. Personally I have endless converters, adapters, port changers, extender cables and more for the most basic of tasks. It’s a bloody nightmare on a personal level. And at an environmental level, just utterly wasteful.

Anyhow, to keep things simple again, there are a few basic adapters you probably need to help you with cloning a hard disk. These are;

- USB External SATA Disk Drive Connector / Adapter Cable (buy here)

- USB External SATA, 3.5” IDE, 2.5” IDE Disk Drive Adapter Tool Kit (buy here)

Connectors, Adapters and Speed

This is a complex topic, and one that quite frankly I don’t have the time to get into the details of – mainly because the manufacturers don’t make this easy and/or make this far more difficult than it should be. You see, we have things such as USB 1, 2, 3, SATA 1, 2, 3, IDE, 1, 2, 3 etc. and I just don’t have the mental capacity to care about too much the differences between these things. I work with what is available and adapt as needed.

The reality is that each and every connector or adapter has a maximum data transfer rate based on the physical materials and hardware that the device has been manufactured from. Everything has limitations and manufacturers don’t make this info easily accessible and/or understandable to the average joe.

Unique IDs of Disk Drives

Right, so now we’re onto the actual hard disk data migration. Now things get fun, and possibly dangerous – so be careful.

Almost every guide I’ve read online skims over this really important point, and it’s probably the most crucial point to take into account – which is to know your IDs, your Unique Hardware Identifier.

For a bit of background as it’s important to understand. For those with a software engineering and/or database background, you will be very familiar with a Unique Identifier for a ‘thing’. Well, with hardware manufacturing, they also do the same thing. For every physical chip that is manufactured, this is generally embedded with a hard coded unique identifier which both helps, and hinders, in many different ways, but that is a topic for another discussion. For example, the sensors that we use on the GeezerCloud product have a Unique ID for every single sensor that we use.

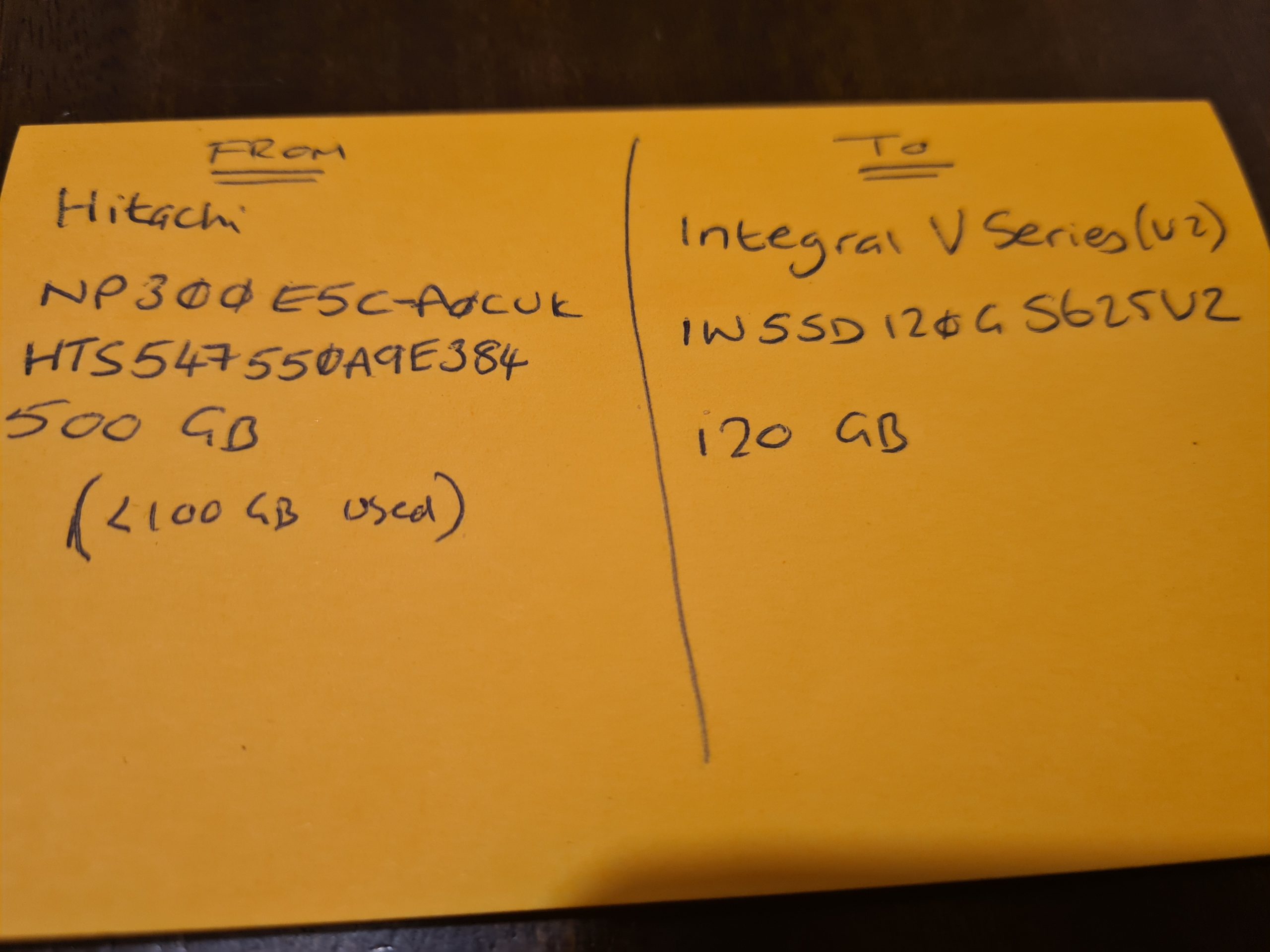

Anyhow, the most important aspect of what I want to mention for this blog post is that all disk drives have a unique identifier. Thankfully this identifier is printed on the physical disk that you have in front of you. It’s printed on the sticker that is physically attached to the disk.

Make a note of the ID of the Disks.

I cannot stress this enough. Make sure you have the IDs of the disks you are working with to transfer data from and to. Make a note of the labels printed on the physical disks so that you can ensure you are transferring data from the right source and to the correct destination.

There is no going back from an incorrect action at this step.

Physical Disks, Partitions and Bootable Disks

Next, before we actually get onto to the migration, it’s important to understand the context. There is a Physical Disk connected to the computer, but then we have Partitions and Boot Partitions to contend with along with both physical and logical volumes. Volumes is just another word for Partition.

This all depends on your specific use case. For example, if the disk you are cloning is from an external USB hard disk, then this probably doesn’t have a bootable operating system setup as it is just there to store basic data. Whereas if you are upgrading your primary disk that runs your operating system, then you will have a Boot Partition which is the part of the disk that runs a piece of software called the Boot Loader which is responsible for booting the operating system you have installed.

For Example;

As you can see above, with 1x physical disk drive, whether that is a Hard Disk Drive (HDD) or a Solid State Drive (SSD), they ultimately have the same bits under the hood to make the disk work as it should based on you requirements – either as a Bootable Disk or a Non-Bootable Disk.

To explain a few concepts;

- The Master Boot Record (MBR) was for disks less than 2 TB in size. In reality these days, most disks are larger than 2 TB in size, so as a general rule of thumb, you are probably best always using Globally Unique Identifier Partition Table (GPT) when managing your disks. MBR has a maximum partition capacity of 2 TB, so even if your disk is 10 TB, the maximum size of any one partition is 2 TB, which soon becomes a pain to manage. Compared with GPT which has a maximum partition capacity of 9.4 ZB, so you’re good for a while using this option

- Primary Partition, this is where your operating system is installed and your data saved

- Another Partition, this is just an example where some people use multiple partitions on the disk to manage their data. In reality, for basic disks you are likely only using one primary partition for standard computer use. When you get into the world of Servers and Data Management, then you end up having many logical partitions to segment your data on the disk for the virtual machines using that data, but that’s out of scope of this blog post.

I have seen this a few times in practice when computers have come my way to fix after a ‘professional’ had already apparently fixed something and clearly it wasn’t done correctly. One recent example was with a 3 TB disk drive, yet only 2 TB of it was available for use as it had been configured with only one partition which had a maximum of 2 TB of size. Clearly the person setting this up didn’t really look too closely at anything they were doing, particularly as their primary ‘fix’ was to replace a 3 TB disk drive with a 120 GB disk drive, then the end person using the machine was sat wondering why nothing no-longer worked and the only way they could access their files was from an external USB drive. #FacePalm

Windows Disk Management

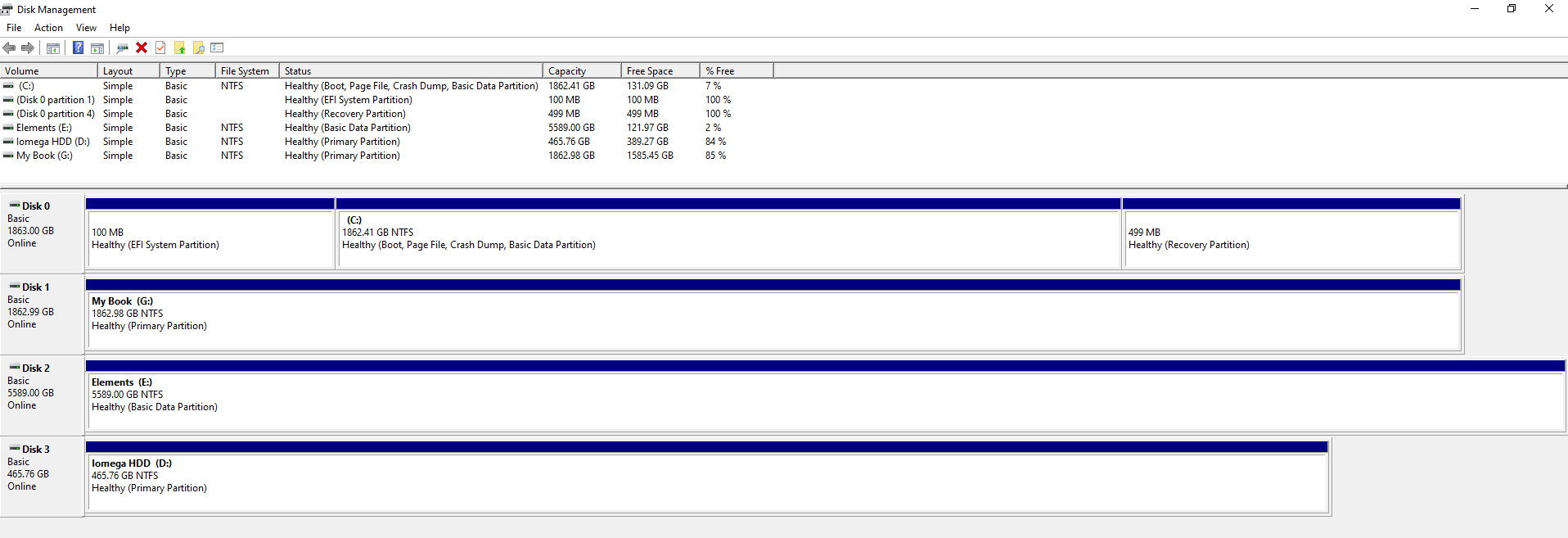

So what does all this look like in practice? Well, thankfully Windows 10 comes with a handy utility called Disk Management. To access this, simply right click on the Windows ‘Start Menu’ Icon and click on ‘Disk Management’.

To bring the above conceptual diagram into focus, here is a real example of what this looks like with multiple disks to a computer;

In the above example you can see that there are 4x disks connected to the machine. One is the main disk used for the operating system and the other three are external USB hard drives in this example. What is a tad annoying with this user interface though is that it isn’t clear exactly which disk is which, so you have to be extremely careful. To any user Disk 0, 1, 2, 3 doesn’t really mean anything so at best you have to try and align the disk sizes to what you can see within your ‘This PC’ on your Windows machine.

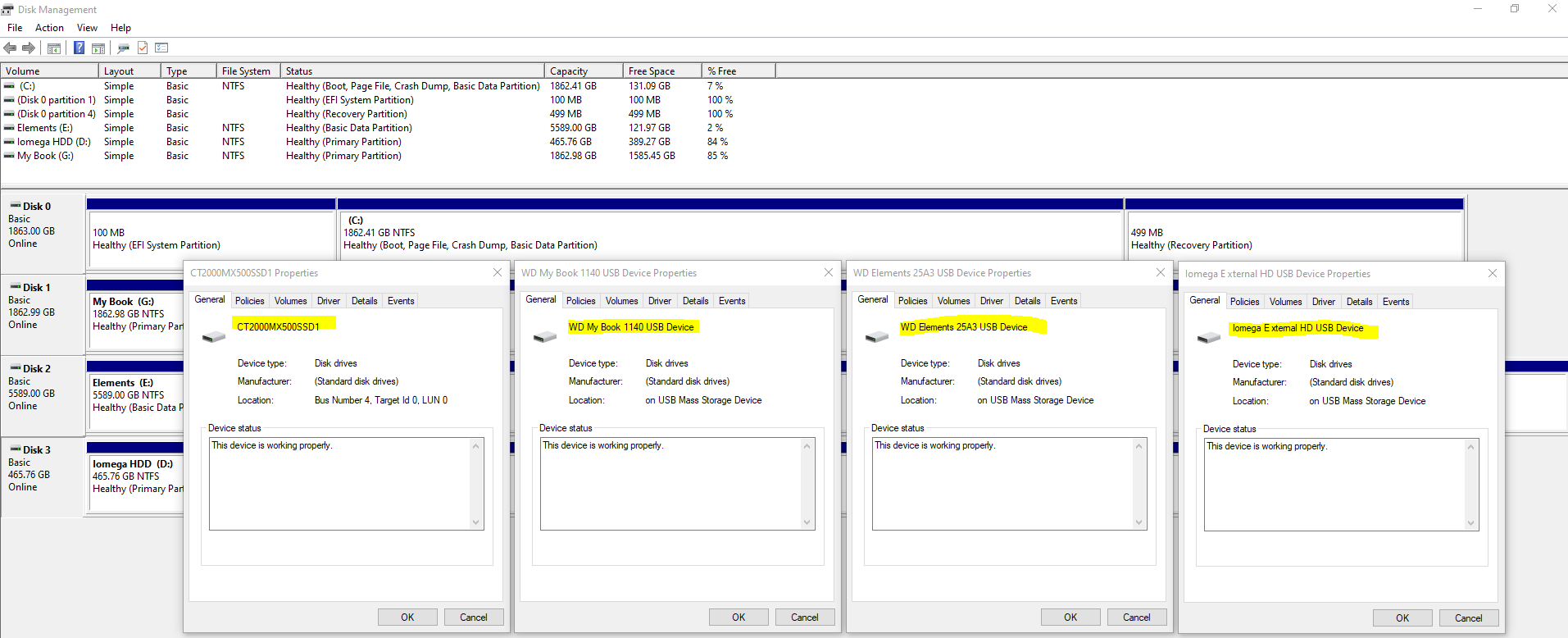

Thankfully when you Right Click on one of the rows and click on Properties, you can see the name of the disk come up as can be seen below;

This info will come in extremely handy when you start plugging in some disk drives that you are going to be working with. It’s essential that you are moving data from the correct disk to the correct disk.

Plugging in Your Disks

Ok, so now we’ve covered off the background topics for how to clone a hard disk, it’s time to jump in and give this a go. You must take this a step at a time to ensure you are 1000% confident that you are sure that you are doing the right thing. As I have said many times already, if you get this bit wrong, it’s going to be very disruptive – particularly if like many people you still don’t have 100% of your data backed up in the cloud.

So, here’s what you’re going to need;

- Old Disk

- New Disk (Contact us if you need us to supply and we can price things up if you aren’t sure what you’re looking for)

- USB External SATA Disk Drive Connector / Adapter Cable (buy here)

- USB External SATA, 3.5” IDE, 2.5” IDE Disk Drive Adapter Tool Kit (buy here)

Make a note of the IDs of your disks from the labels on the physical disk drive. You should see these exact names show up in Windows Disk Management Utility Software. It is these IDs that you will need in the next step to make sure you are cloning the data from and to the correct disks.

One item to note is that if you are using a brand new disk for your New Disk, then you will need to Initialise the disk using GPT via Windows Disk Management Utility Software when prompted once it is plugged in. For disks that you are re-using then this initialisation step usually doesn’t appear. For new disks you will also need to right click on the unallocated area of the disk and select New Simple Volume, then give the Volume (aka. Partition) a size and a Drive Letter then you can format the new partition so you can use it going forwards. Then the drive is ready for use.

Clone Hard Disk Software

There is a small handful of software available both commercially and open source for cloning disk drives, with significantly varying usability aspects. For simplicity, we’re going to take a look at one of the easier to use pieces of software called Acronis True Image for Crucial.

Aconis is a commercial product, but many manufacturers have a free Clone Disk feature within Acronis, such as for Crucial Disk Drives the above software works. There are a lot of makes/models of disks on the market, so if in doubt about what software works best with your hardware, then contact the disk drive manufacturer directly via their support channels and they can advise best which software works best with your hardware.

There are also lots of super technical open source options available, but personally I’ve just not had time to play with these since this is fundamentally a basic copy and paste job fundamentally so it should have a user interface for allow anyone to do this kind of thing in my opinion.

Here are a few images of the setup I was playing with for the purpose of this blog post;

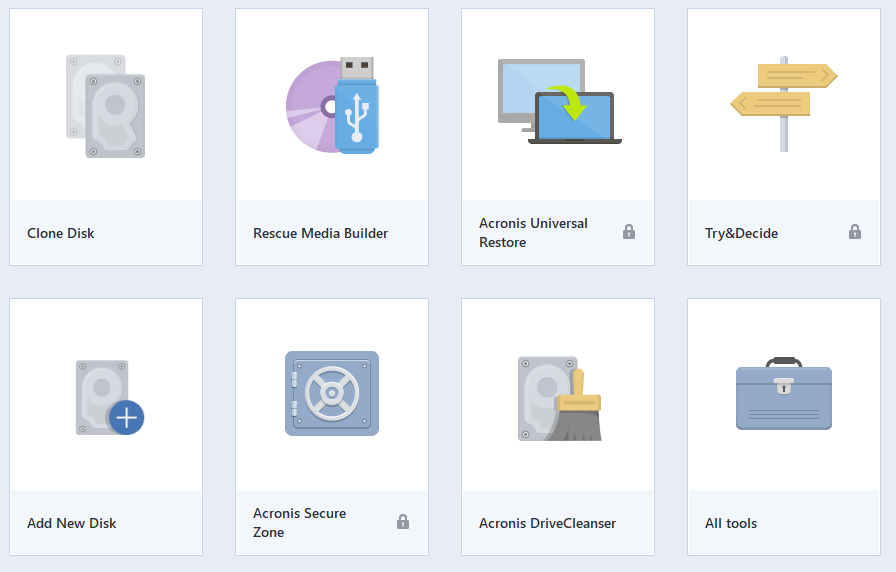

Open Up Clone Disk Tool in Acronis

When you have Acronis open, select the Clone Disk tool. Note, this can take a while to open up, so be patient.

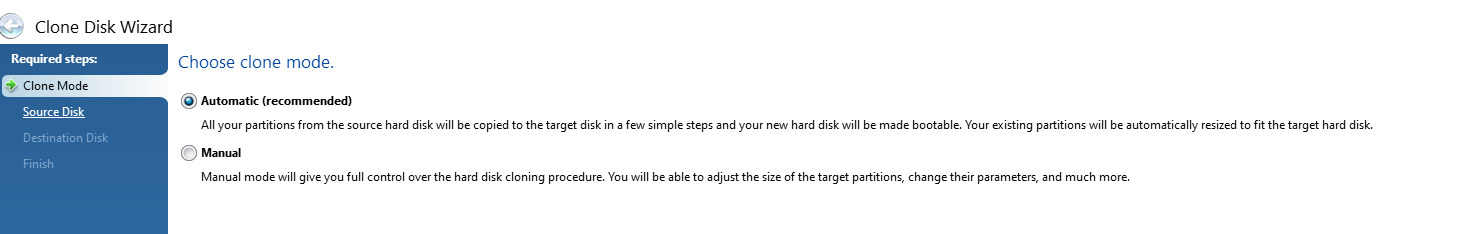

Select Automatic Clone Mode

This is the mode that is most common to use which handles everything in the background for you. The Manual mode gives you much more control but can often be a bit overwhelming if you aren’t too familiar with some of these concepts.

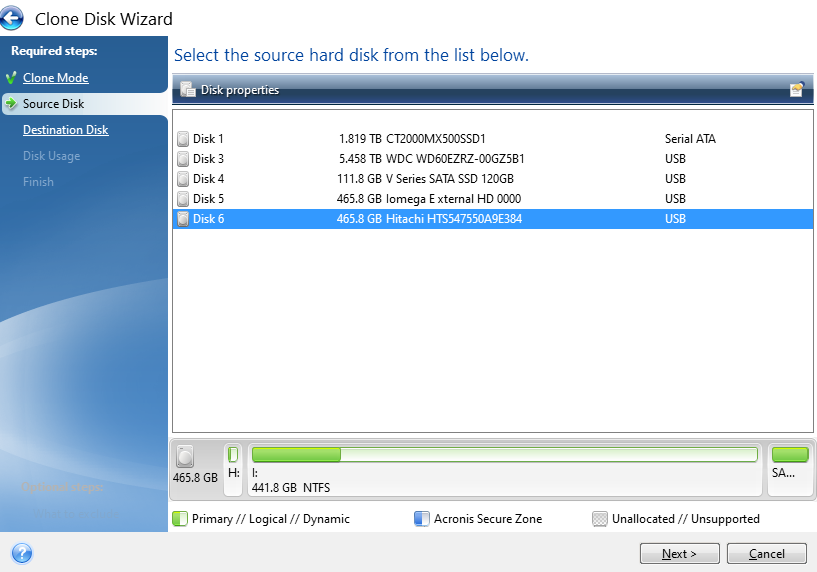

Select Source Disk

This step is particularly important, make sure you select the correct ID that is printed on the hard drive sticker so you are confident you are moving data from the correct disk drive.

You’ll notice the handy info that Acronis displays at the bottom which shows how the partitions on the drive are currently set up and what is and isn’t being used. This comes in very handy in the next step, particularly as in this case the data is being migrated from a 500 GB HDD to a 120 GB SSD. Your math is correct, that doesn’t fit – but – Acronis is smart enough to only transfer the data that is being used which means that in this scenario the data will fit.

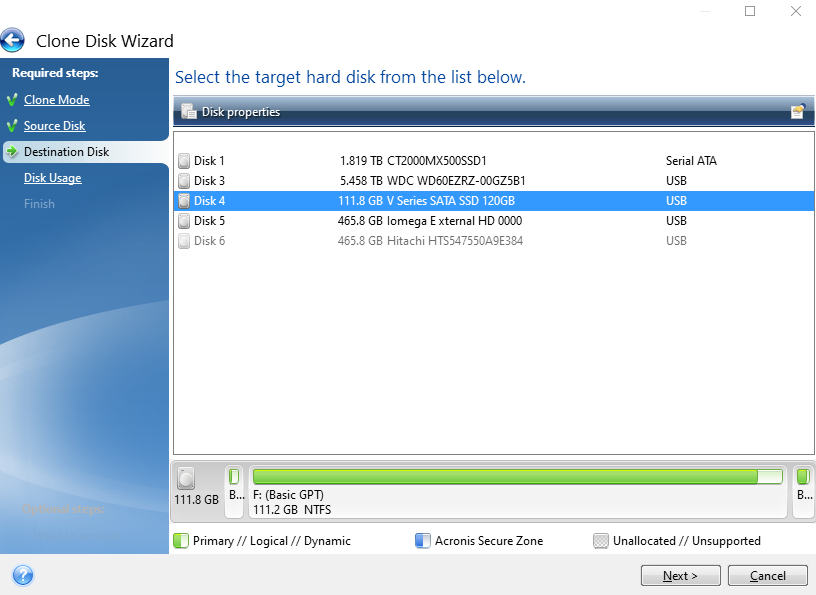

Select Destination Disk

Same as the previous step, make sure you are selecting the correct disk based on the IDs of the disk that is printed on your physical disk.

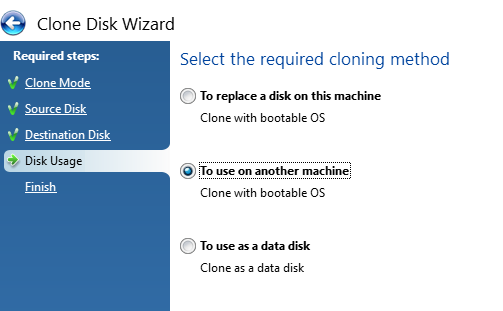

Select the Cloning Method

Next, select the cloning method you are doing. In my case both the old and new disks are connected via USB and are going to be used on another machine, not the machine that Acronis is installed and being run from. Generally speaking, when disk drives start failing, the machine they live in also becomes fairly unresponsive and/or just extremely sluggish. So it’s often easier to whip out the old disk drives and get them plugged into a decent computer that can do the grunt work.

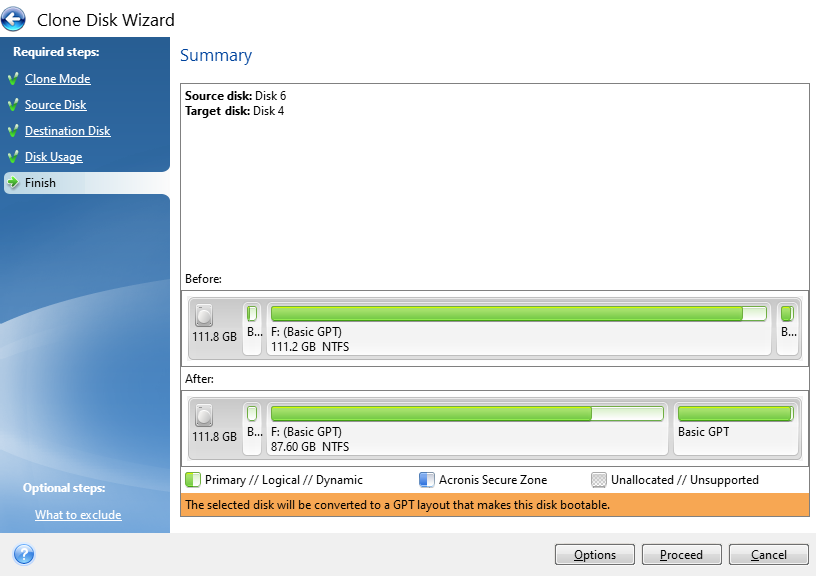

Confirm Settings and Start the Cloning Process

The final step is just confirming what your new disk will look like both at present and after the conversion process. In this example, this is an existing disk that is being flattened and re-purposed which is why the before info shows that the disk is full. If you are using a brand new disk, this will show up mainly empty as there will be nothing on it.

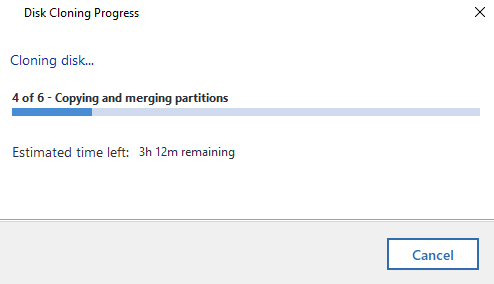

Now it’s just a case of sitting back and waiting. I’ve mentioned already Acronis is a slow piece of software for whatever reason. Just getting to this point probably took around 45 minutes believe it or not. The cloning process takes even longer. So make sure everything has plenty of juice to keep the power on throughout the process or you’ll end up losing a lot of time going through this process again.

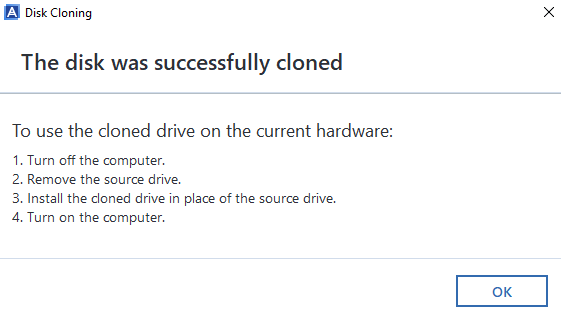

Disk Clone Successful

Woo! Finally, the cloning process has been complete. Now it’s just a case of plugging the new disk drive back into the computer you took the old one out of and everything should be back to normal, working fast again etc. If you do get any problems with this point, then generally the clone will have failed, even though Acronis says that it has worked. i.e. missing a bootable sector or some other form of corruption that is going to be near impossible to get to the bottom of.

Backups, Cloud, Redundancy Etc.

Ok, so we’ve run through the process of cloning hard disks either from HDD to HDD, HDD to SSD or SSD to SSD. Whatever your situation has been. What we haven’t covered off on this blog post yet is around backups, cloud and data redundancy etc. So let’s keep this topic really simple… your hard drives will fail at some point, so plan for it.

Use cloud service providers for storing your data, they have endless backups in place that are handled for you automatically without ever thinking about it. If you only have your data on your main hard disk in your computer, there is a chance that when your disk fails, you will permanently lose your data. Do not go backing up important data to external hard drives, this is manual, error prone and is still likely to result in some data loss for your data when one or more of your hard drives fail.

This is a topic that I could go into for a long time, but will avoid doing so within this blog post. Instead, let’s just keep things simple and ensure your data is backed up to the cloud. And make sure you can easily recover from a failed hard disk and be back up and running within hours, not weeks.

Notes on Failing Disks

Important to note that if you are working with a failing disk, then you can pretty much throw all of the above out of the window. Give it a go, but it’ll probably fail. You are probably best off getting a new disk drive and installing Windows 10 from scratch then you can copy the files over that you need (and backing them up to the cloud!). It’s a bit painful doing this but often it’s the only route when the disk drive has gone past the point of no return and is intermittently failing and doing random things. I’ve seen random things such as monitors flashing on/off with the Windows desktop going blank then back again on a repeat through to disk recovery software failing when it tries to read one single bit of data on the disk, usually about 95% into the process. It’s always best not to get to this point. Some other nuances I’ve seen is that BIOS wasn’t detecting the disk after an apparent successful clone, yet I could see the drive in Windows Device Manager when plugged into another machine, but it wasn’t showing up in Windows Disk Management. All very odd.

When thing get to this point, it’s time to just give up on the old disk, get Windows installed on a brand new one and salvage what you can. Learn your lesson and don’t make the same mistake twice. There are advanced recovery (and costly) options available to do deep dive recovery of data, which again on failing disks can even still be a bit hit and miss so you could be throwing good money after bad trying to recover this data, but it all depends on how important that data is to you.

Check What Your Old Disk is Using – GPT or MBR

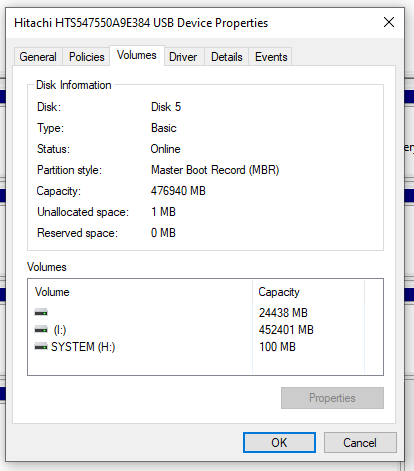

Something we didn’t go into in too much detail so far but is important to mention. GPT VS MBR – Make sure you check what the old disk is configured as. Or you’ll be repeating the processes again, or be forced to use a commercial bit of software to change GPT to MBR or the other way round. To do this, within Windows Disk Management, simply Right Click on the old drive and select Properties, then click on the Volumes tab where this info will be displayed. In this case we can see that the old drive is using MBR, so it’s best to configure the new disk drive also to use MBR because the computer this came from could (and likely will) have certain limitations at the BIOS layer about if MBR or GPT is supported (aka. UEIF Mode either Enabled or Disabled).

Note, Acronis is a pretty dumb and opinionated piece of software. It assumes that the Destination Disk Partition Mode (MBR VS GPT) is determined purely based on the computer that Acronis is running on. This is dumb, and quite frankly a fundamental flaw in the software in my opinion. In the vast majority of use cases in my experience, the Source Disk and Destination Disk are going to be plugged into an independent computer that is merely there to perform the copy and paste job.

MBR VS GPT is a Legacy VS Modern topic that is beyond the scope of this blog post. But what is important to note beyond the disk drive is that this comes down to the Motherboard’s BIOS Settings in relation to UEIF which is either Enabled or Disabled. Even still, there can be many compatibility issues in this space.

Sometimes, it’s just more effort than it is worth trying to upgrade a computer though. If it’s old, the Old HDD is old, then all the other components are old and slow. Sometimes it’s just more economic to throw away (recycle) the old and get a brand new computer and/or start with a fresh installation of Windows and go from there.

There are many bits of software that can help with cloning disks include: Clonezilla, Macrium Reflect Free, DriveImage XML, SuperDuper and many more. Many come with free basics and trial periods, but generally if you want to do something in full with an easy user experience, then you’re going to be using the commercial offerings.

After personally getting rather frustrated with Acronis, I decided to have a little rant on the Acronis Support Forums. Summary being “Unfortunately this is very unlikely to change for all users of Acronis True Image! This is because Acronis no longer support or develop this product.” And “The MVP community have been asking for this for some years but without any success.”. Not a very positive message, but at least an honest one from a senior member of the community given the lack of engagement from Acronis directly.

Summary

Hopefully this has been a helpful and detailed blog post for how to clone a hard disk drive (HDD) or solid state drive (SSD) and how you can handle this process for either failing disks or just upgrading disks to newer, faster and larger models.

Please take care when performing these actions and if you aren’t sure what you are doing, then leave this to the professionals. There are a lot of nuances with these types of actions which can be extremely destructive if you get this wrong. Be careful.

Michael Cropper

Latest posts by Michael Cropper (see all)

- General Scheme of the Regulation of Artificial Intelligence Bill 2026 - February 4, 2026

- WGET for Windows - April 10, 2025

- How to Setup Your Local Development Environment for Java Using Apache NetBeans and Apache Tomcat - December 1, 2023